The Yoga Sutra, the preeminent text on yoga consists of four padas—or sections—each containing a number of individual sutras. In his Yoga Sutra, the sage Patanjali sheds light onto the workings of the human mind, the specific and particular brands of suffering that we unwittingly impose upon ourselves, and the full picture of healing and resolution for our suffering. Patanjali has offered a codification and thorough description of the practice of yoga, and the means for relieving the inevitable suffering of the human mind that is not aware of its inherent depth of intelligence and power—Pure Unmanifest Awareness. Patanjali provides us with a precise outline for practice.

I. Samadhi Pada defines yoga and puts the practice in perspective. We are introduced to the ways that our individual minds cloud our experience of the true nature of life.

II. Sadhana Pada covers the yamas, niyamas, asana, and pranayama. It provides the necessary framework for effective practice. Pranayama is the gateway to the inner world.

III. Vibhuti Pada takes over where Sadhana Pads leaves off, honing in on the more subtle aspects of practice. Beginning with pratyahara, it addresses the ways to continue to refine our awareness, addressing, dharana, dhyana, samadhi. This pada moves into the realm of samyama—the integration of the three.

IV. Kaivalya Pada: In the final Pada, Patanjali brings together many of the more esoteric and sometimes difficult to understand teachings of the practicality of practice. Although it may read as densely philosophical, it is rich with subtle practices of inquiry. Patanjali invites us in even deeper. When awareness has been mostly cleared these inquiries can bear fruitful knowledge and the inquiry itself continues to refine and hone the individual consciousness—making it a more and more radiant and open receptacle of Divine Light.

At the beginning of the Yoga Sutra, Patanjali lays out the context for practice. He encapsulates his entire message in the first three sutras, immediately addressing the need for practice, what the process requires, and the goal. If the first three sutras are intriguing enough, one will practice. If they are not, there will be little motivation to continue.

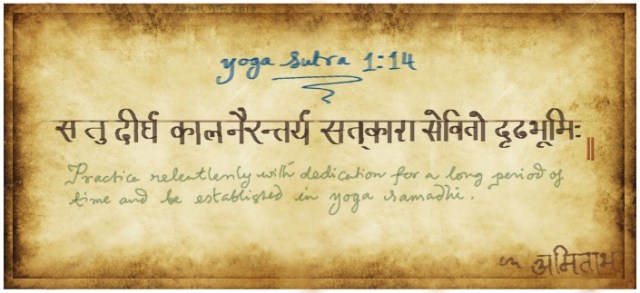

Sutra 1:1

atha yoganuśhāsanam

Now begins the instruction on the practice of yoga.

Atha communicates the auspicious nature of the teachings that are about to be elucidated. Most commonly translated as “now”, atha is also the expression of the self-luminous guiding Intelligence that resides within the heart and mind of every human being. By using the term atah to initiate his treatise on yoga, Patanjali sets the stage for the comprehensive message that will follow: we are all radiant beings, our very nature is manifesting into form with brilliance and power, and it is possible to recognize this directly. The meaning of “now” is in itself auspicious. Now is the present moment, the place of no future, no past, only this exact unmoving place of presence and radiance. Now describes the unified state of mind. In the first sutra, Patanjali has created an inclusive container for all the teachings that are to come.

He continues to say that “now”, perhaps you may be open to undertaking the inquiry that will reveal the core of being to your conscious awareness. The implication is that now one may actually be ready to practice yoga. One has tried everything else, and finally understands the futility of looking for satisfaction within the arena of the solely personal field of individual mind. Having seen and tried every machination of effort to gain contentment in a life perceived through the most superficial layers of consciousness, one is now ready to seriously embark on the study of yoga.

With the term anuśhāsanam, Patanjali is stating emphatically that yoga means practice. Patanjali lets us know right away that the Yoga Sutra is not simply a philosophical text. Patanjali is stating right at the start that yoga requires practice and the strong implication is that practice will require commitment and fortitude.

Sutra 1:2

yogash chitta vritti nirodhah

Yoga is the mastery of the fluctuations and roaming tendencies of the mind.

In this sutra, Patanjali states the problem: vrittis—habitual movements of individual consciousness that rise and fall endlessly in the mind. They are swirling thoughts and feelings, usually associated with egoic desires and attachments that pull individual consciousness into vortexes of self-involvement, effectively obscuring the field of consciousness in which they are functioning.

The effect of being caught in the pull of the vrittis is that the individual is drawn into the mistaken belief that the vrittis themselves define an ultimate reality. The individual ego-mind adopts an erroneous belief that it is the ultimate observer when in reality, it is simply another fabrication of thoughts and self-constructs.

Vrittis have the power to keep us locked into the smallness of self-consciousness and obscure the larger framework of Universal Awareness. Patanjali informs us that the lack of resolution of the vrittis is obscuring our direct perception of their own source—Pure Awareness. We are told that we need to gain mastery over our mind’s incessant movement in order to see our thought processes and uncover the nature of individuality if we are to accomplish the goals of yoga.

The ego-construct of self-identity usurps the role of the ultimate Seer and thinks that it is the “who”, that is perceiving all of life. This mistaken identity needs to be cleared up in order to be able to see life as it actually is.

Sutra 1:3

tada drashtuh svarupe vasthanam

Then the Seer becomes established in its essential nature.

The third sutra tells us what happens when we gain resolution and calm the vrittis in the mind. “Seer” is the term Patanjali uses to denote Pure Unmanifest Awareness. Patanjali tells us that the Seer is the only true observer, and that the egoic thinking mind is sorely deluded with its own self-importance. When vrittis are allowed to run rampant—the radiance of Awareness barely shines through the confusion and clutter in the mind. The field of individual consciousness is clouded with thoughts and feelings, and the person is thoroughly distracted from noticing the deeper aspects of existence.

When the vrittis are clarified, they no longer cloud individual consciousness. The recognition of the vrittis for what they are paves the way for the light of awareness to shine in its proper place—everywhere—and the suffering of excessive self-involvement to end. It is a matter of putting things in their rightful place, living from the perspective and direct experience of Pure Awareness as always present and always containing and supporting everything else. Patanjali is letting us know that as we practice we will become increasingly able to choose to perceive life from the vantage point of the bounty of vastness, rather than from the limited and small personal.

As the text continues, Patanjali methodically and brilliantly lays out the means of practice, from the most basic understanding of how the human mind becomes ensnared in delusion and how to proceed to clear up the confusion, and finally allow our human consciousness to witness directly—and live with—the Divine Radiance of Being.

“Intensity of practice and renunciation transforms the uncultured, scattered consciousness, chitta, into a cultured consciousness, able to focus on the four states of awareness. The seeker develops philosophical curiosity, begins to analyze with sensitivity, and learns to grasp the ideas and purposes of material objects in the right perspective. Then he meditates on them to know and understand fully the subtle aspects of matter. Thereafter he moves on to experience spiritual elation or the pure bliss of meditation, and finally sights the Self.” B.K.S. Iyengar— Light on the Yoga Sutras

Practice. Practice. Practice.

Clearly, yoga has lofty aims. For most of us, it is not likely that we will just drop into the state of Self-Realization or Unity Consciousness by accident. Most of us need to practice. Due to the conditioned patterns and limitations that so thoroughly cloud our minds, we need to know methods for practice. We find methods in the yoga sutras.

We know the eight limbs as: yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi.

YAMAS AND NIYAMAS

The yamas and the niyamas—the first two of the eight limbs—set the stage for fruitful practice. They make it possible for us to direct our minds to the following six limbs and lay the foundation for successful practice. Their ethical principles contain our inner and outer actions and provide a map for behavior that is conducive to spiritual study. We learn to be kind, truthful, not to steal or hoard, and to cultivate the movement of our life in the direction of greater clarity and truth. We learn to practice personal cleanliness and to pursue purity in thought and action.

We commit to studying the interface of the personal and the Universal with zeal and passion. And we learn not to take our selves too seriously. We perceive that all action is driven by Universal Awareness and that we are simply vehicles and vessels for the universal actualizing into form.

Without adhering to the yamas and the niyamas our minds are so preoccupied with extraneous thinking that it can be very difficult to go any further. If you are worried about how you shouldn’t have said that mean thing, you wish you hadn’t claimed responsibility for something you didn’t do, or you are preoccupied with thinking that someone else has something more or better than you do, you won’t find it easy to focus on the more subtle aspects of life and practice.

In order to go more deeply within, one must cultivate qualities of purity and cleanliness—inside and out—and especially in the arena of the mind. Purity of mind comes from the ongoing inquiry into what is true and what is not. It involves the threading out of destructive patterns of thinking and negative actions that inhibit our clear vision of life as it actually is.

We need to begin to understand our rightful place in the world, practicing contentment, self-discipline, and self-study. And we need tapas. Without tapas—the burning desire to know Truth—we won’t find much success in practice. We must be driven. The degree to which we are driven is the exact degree to which we garner the gifts of yoga. Tapas keeps us on track. It inspires us to study the spiritual texts, to learn from qualified teachers, and to practice self-inquiry with a keen and incisive mind.

Last, and definitely not least, we must learn to let go of the desire to claim the fruits of our own actions. We need to learn and know, as an abiding reality, that we are really acting as servants of the evolutionary movement of divine life-force. Acting in accordance with right and good, we assume our natural and authentic place in our own lives and in relationship to the good of the whole. Our thought, deed, and action, spontaneously become aligned and in accordance with the universal evolution toward the manifestation of greater clarity and light into the field of form.

We learn to perform actions and work in the world, not for our own personal gain, but as an offering to the Divine. This is not to say that one should not provide for oneself, one’s family, and so forth. Providing for oneself is support for strong and useful action. Personal care is necessary for one to be a vital part of the movement to expand truth and love into the world at large. But the petty kind of egoic attachment to one’s work and offerings is not productive to spiritual growth and does nothing to clear the way for effective action in the direction of good.

ASANA, PRANAYAMA, PRATYAHARA

The next of the eight limbs is asana flowed by pranayama, and pratyahara. In Embodyoga® we take an approach to asana which encompasses all of the eight limbs into practice. Without adhering to the principles of the yamas and niyamas we know that we are just too distracted by the ramblings of a dissatisfied mind to engage in the deep inquiry of serious practice. We manage our ethics and our conduct in daily life, continuously inquiring into whether we are living up to our own personal standards and endeavoring to improve where necessary. Then we can settle in to have a thorough practice—on the mat, seated in pranayama, or meditation.

In Embodyoga® we actively weave pranayama and pratyahara into every moment of practice. Attending to our breath, we use it as the key vehicle for allowing the conscious mind to descend into our subtle layers of experience. Since pranayama helps to soothe the nervous system and simultaneously enliven feelings of inner comfort, it paves the way for pratyahara. Pratyahara—the turning of the sensory faculties inward—opens the doors to the inner world. Sensing and feeling we dive within.

We practice self-acceptance, non-judgment, and discrimination in everything we do. We enlist our powers of perception to delve deeply into our structural, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual selves. We do this through the process of Embodied-Inquiry. We notice, feel, and touch. We move. Using a template of inquiry that takes us from the obvious layers of perception to the most-subtle, we are naturally drawn into the complete field of body-mind-spirit.

DHARANA, DHYANA, SAMADHI

Dharana, dhyana, and samadhi describe the process and result of meditation. Dharana is focusing and collecting the flow of consciousness into a single direction, and dhyana, often described as meditation is allowing and surrendering to natural flow of the mind into its source, a place of greater comfort and joy. In fact, yielding to Self. Samadhi is the dissolving of the individual mind into the universal. Dharana is a practice of effort. We do it. Dhyana is a practice of surrender. We yield and allow the gravity and comfort of Awareness to pull our individual consciousness inward. And Samadhi is the unified state of individual consciousness fully dissolved into the universal field of Awareness.

We enlist an object of meditation. The object may be a particular yoga posture or form. It may be an organ system or glandular structure. It may be a feeling or a particular pattern of thought. We may use mantra or inner sound. We may focus on an aspect of the fluid body moving, the organization and consciousness of organ and bone marrow working together, an inquiry into a specific movement or developmental pattern for increasing whole body-mind integration. We inquire into the relationship between Self, self, and others, and how those relationships affect our expression in movement, thought, and action. We explore how the elements, earth, water, fire, air, and space express within and without. We follow our senses inward to experience directly layer upon layer of subtle expression within our own body-mind-spirit world.

In choosing an object for our inquiry we utilize the basic tools of asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi. We are meditating on the body and the nature of the body is exactly the same as the nature of everything else. In other words, anywhere we skillfully inquire we will arrive at the same exact place: Pure Radiant Awareness. Skillful inquiry takes a fine balance between the effort and surrender: Dharana—we take the right direction collecting our awareness to the object of our meditation. Dhyana—we allow the effortlessness of descending to take over and are naturally drawn toward the subtle qualities of the object (whatever it is). Samadhi—the spontaneous experience of Unity.

Through the repetition (practice) of Embodied-Inquiry, we expand our ongoing ordinary range of conscious experience to include not only the individual but the universal as well. We clarify the personal consciousness by observing it over and over again. Observation reveals its nature. We begin to recognize directly the actual context of the thinking mind and the feeling body. It becomes our direct and immediate experience. This is a profound and dramatic shift in human consciousness. The new perspective cures the petty self-involvement that we suffer at the hands of ego dominance and the incessant sway of unchecked vrittis.

PRACTICALITIES

In Embodyoga® all that we do is designed to hone awareness. This applies equally to our study of philosophy, pranayama, asana, meditation, and our actions in the world. We don’t separate any of our practices from life. We use them as tools for living a fuller and richer life, a life that includes the personal and the universal as directly perceived realities. The universal vision puts the personal in its proper place so that we can enjoy the personal for what it is while experiencing the wonder of the whole.

- Embodyoga® requires effort to practice and surrender to feel the results. We must take the right direction to delve within, but then we need to let go and surrender to the natural tendencies of body and mind to find greater comfort and nurturance within can take over. Too much effort keeps us on the surface, and too little effort yields no results. Abhyasa and vairagya—practice and surrender are our guides.

- Establish a strong commitment to practice. What is important to you? Do you actually want to take this on? Have you had enough of being swept around from painful feeling to painful feeling, never understanding the context of why you are alive?

- Are you willing to take responsibility for your life, who you are, and what you do?

Chose a regular place and time. Just do it.

Thank you Patty, I seriously needed this reminder. In a world like this, it is too tempting giving up our integrated practice. These days, I spend most of my practice sitting in contemplation but not even of my body but of my mind. I have developed the habit of practicing asanas only when my body cry for it, after hours and days of just using my mind. How important it is to explore the truth, Satya, in every cell of our bodies and let that shape our perception of the reality.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Respect and Permission in Yoga—Yamas and Niyamas | Embodyoga®