Yoga is a process of differentiating and unifying. We differentiate layers of consciousness and structure, we inquire, we analyze, and we find our way back to unity. In looking at the glandular system we are called upon to investigate the glands themselves, as well as how they relate to the subtle energy system of chakras and nadis.

Yoga is a process of differentiating and unifying. We differentiate layers of consciousness and structure, we inquire, we analyze, and we find our way back to unity. In looking at the glandular system we are called upon to investigate the glands themselves, as well as how they relate to the subtle energy system of chakras and nadis.

In studying the glandular system in Embodyoga® we look at its support for body and mind, and especially its importance in all yoga practices. We focus primarily on the effects the endocrine glands have on our experience—how they support us in asana, in posture in general, and how they affect our experience of self. We look at how the glandular system provides a suspension system for our core, and how the innate intelligence of individual glands is manifesting into form and functioning. Not all of the structures we look at are technically considered to be glands. Some are bodies, nodes, and one has yet to be recognized at all. We are loosely calling all of them glands because they do relate directly to the yogic chakra system and the yogis have classically placed what they have called glands as the structures that correlate with the chakras along the spine.

glandular system provides a suspension system for our core, and how the innate intelligence of individual glands is manifesting into form and functioning. Not all of the structures we look at are technically considered to be glands. Some are bodies, nodes, and one has yet to be recognized at all. We are loosely calling all of them glands because they do relate directly to the yogic chakra system and the yogis have classically placed what they have called glands as the structures that correlate with the chakras along the spine.

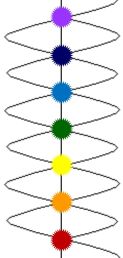

The radiant core of our individual being is felt within as sushumna nadi. The embodiment of sushumna supports our personal relationship with refined awareness and is our active connection to Source. Our latent qualities and traits—all the things that make up our personal selves—are contained within this embodied core and emanate out through the chakras, the energy vortexes that form along our central channel. Each chakra has one or more glands that relate to it. Each gland is felt to contain and express subtle intelligence that is manifesting from the chakra and expressing outward into the full expression of our individuality. Due to their close relationship to core, our glands naturally emanate more light than some of the denser body tissues. For example, glandular expression has less gravity than that of organs. Organs feel more voluminous and heavy in the body. The levity of the glands balances the weight of the organ body.

Glands function as a single integrated system while maintaining their individual processes. As a suspension system from head-to-tail and tail-to-head, they offer light support along the vertebral column and through our soft tissue core. The brightness that emanates from them radiates in all directions, giving levity and resilience to the neighboring tissues. Individually, each gland secretes its particular hormones and stimulating agents into the surrounding fluids on their way to receptor sites in target cells throughout the body.

Each gland has correlations with different aspects of the skeletal system. This means that the gland and its skeletal correlate are mutually supportive. Glandular support in the skeletal body gives a bright clarity to our experience of bone. This integration of glandular and skeletal systems offers qualities to bone that can make our yoga postures look and feel lighter and more effortless. The glands are always suspending themselves and the tissues around them. They are in constant communication and relationship with one another. They levitate the denser structures of the body and create an anti-gravity feeling of support through our core.

DIAGRAM: GLANDS AS A SUSPENSION SYSTEM FOR THE BODY

It may be useful to begin exploring our glands through images of faceted jewel-like structures that refract and emanate light through themselves and the body in geometrical rays. This is in keeping with the embodied experiences they offer and the kind of support they provide. Ideally, the inner sense of our glands feels lively, vibrant, responsive, glistening, and self-aware.

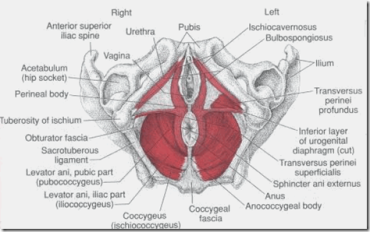

Perineal and Coccygeal Bodies

We begin at the bottom of the system with the two glands that relate to our root chakra, the perineal and coccygeal bodies. The perineal body, at the center of the pelvic floor, is the home of apana vayu in the subtle body. Apana is the vayu, the wind of life force, that draws inward and downward. Apana gives the perineal body a strong pull—drawing life force down and into itself, and also when appropriate, downward and out of the body. It tethers the entire glandular suspension system. The mammillary bodies at the crown provide the opposing directional pull—heavenward. As you can see in the image above, the perineal body is right at the center of the diamond shaped pelvic floor, situated just between the anus and the genitals. For a long time the perineal body was not recognized by western science. Since it is encased in connective tissue it was simply missed.

The perineal body provides a precise and clear, deeply condensing point to which everything is secured. In addition to its downward condensing pull we find that it is highly expressive as well. The first chakra is organized here in the pelvic floor. It has four petals that open from its center. This is not unlike how the perineal body feels when it is allowed free expression. In full expression the perineal body spreads its readiness and appreciation for being alive through the pelvic floor region, the legs, the feet, and into active relationship with earth. The perineal body is as excited about moving into form as it is about condensing into its own dark gravitational field. Its gravitation and density pulls spirit into the possibility of manifestation, and then having convinced spirit to play, its commitment to life explodes into function and form. The perineal body rises in mulabandha. But without its partner, the coccygeal body, it is rising in a vacuum. The coccygeal roots the perineal to the earth.

The coccygeal body is a small mass of irregularly shaped glandular and vascular tissue about 2.5 mm in diameter. Imbedded in fascia, it is tucked right inside the arc of the of the coccyx. It has a tiny tail that points upward. The coccygeal body consists primarily of glomus cells. Glomus cells are oxygen receptors…oxygen receptors at the tip of the tail. This is interesting in breathing. In embodied explorations we have found that full breathing is initiated by a pulsing of the coccygeal body that can be clearly felt by the practitioner. It can also be felt by a sensitive observer. Placing the palm of a hand just above the skin at the coccyx, one can feel a clear puff of breath into the palm right at the initiation of inhale. When the coccygeal is awake and functioning fully we can feel a breath of fresh air expanding right between the gland and the coccyx behind it.

The coccygeal body has very different intelligence and energy than its partner gland, the perineal. While the perineal body grounds the suspension system like a dense black hole of gravitational force, the coccygeal body has a much lighter, directional, and downward rooting energy. The coccygeal body is like a seed that sends a lively tap root spinning out of itself and into the earth in spring. Light and bright, whereas the perineal body is dense and dark, its lively energy flies off the tail and finds it’s way toward and into the earth. Although it is flexible and tender it can easily penetrate the hardest, driest earth.

The actions of the coccygeal and perineal bodies create balance in the pelvic floor. The perineal is dark and the coccygeal light—like the “ha” and “tha” of the root chakra. Both are strong and dynamic, and together they make the whole. The pelvic floor forms the structural foundation for mulabandha and for an effective mulabandha the awakening of both is necessary. Without the earthward action of the coccygeal, the upward lifting of the perineum has no ground. When the coccygeal is awake, the perineal can rise. Even as the perineal body rises in mulabandha, it maintains its condensing power.

Skeletally, these glands relate to our feet—downward through the toes, toe balls and heels and upward through the arches.

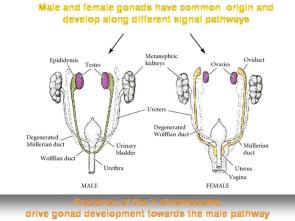

Gonads

The gonads are paired glands. The embodied place for gonads is the same for both males and females, in the two sides of the pelvic belly region—the actual position of ovaries in women and the place at which the vas deferens loops around for males. In utero both male and female gonads were right here in our side pelvic bellies. It isn’t until just before or after birth that the male testes drop down and find their way out of the body cavity.

Gonads relate to the second chakra and their element is water. They embody emotionality, creativity, regeneration, fluidity, and desire. In movement they create levity and a sense of three dimensional radiance that forms a pivot point around which each pelvic half can rotate. They support the hip joints by keeping weight out of them. Skeletally the gonads relate to the ankles and the pivoting options in the pelvic halves are reflected in the ankles as well. The harmony or disharmony of the movement of gonads and ankles can be an interesting exploration in asana. Weak ankles are common and can be a reflection of an imbalance in the clarity of life force expressing from the gonads. Collapse or hardening of the gonads limits the life force in the pelvis and can dis-integrate the connection from pelvic halves to feet.

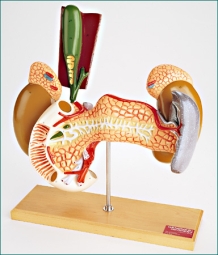

Adrenals and Pancreas

The adrenals and pancreas are the glands of the manipura, or third chakra—fire. We consider the adrenals to be the lower manipura chakra—about the level of the belly button navel (which is the adrenal reflex point). They are concerned with personal safety and staying stable on the earth. Self definition and the qualities of “I, me, and mine” find their home in the lower manipura.

The adrenals and pancreas are the glands of the manipura, or third chakra—fire. We consider the adrenals to be the lower manipura chakra—about the level of the belly button navel (which is the adrenal reflex point). They are concerned with personal safety and staying stable on the earth. Self definition and the qualities of “I, me, and mine” find their home in the lower manipura.

Pancreas is the upper manipura. Pancreas is concerned with spatial reach and an internal movement from being all about “me” to relating to community and other.

Adrenals, known for their hormonal secretions that stimulate the flight, fight, freeze response respond to our perception of safety and comfort. Governed primarily by the sympathetic nervous system, our adrenal response is important for keeping us alive and letting us know when we need to take fast action to be safe, jump out of the way of an oncoming car, avoid a dangerous person, or respond appropriately and quickly to any immediate danger. In health our adrenals assist in providing us with a balanced and alert state of body-mind. Healthy adrenals have life force to spare and are useful when we need them, but don’t need to be constantly pumping out hormones creating hyper-vigilance in the body when it isn’t warranted.

When we are under chronic levels of stress due to real or imagined situations, when we do not feel safe in an ongoing way, our adrenals can release excessive amounts of their hormones and create agitation and tension throughout the entire system. Even if the threat is not real, but is perceived to be real, these hormones will be produced. This leads to high levels of stress hormones in the body that keep us on continual alert and can eventually lead to depletion and exhaustion of the adrenal system.

Skeletally, adrenals relate to the knees. The knee to adrenal connection that we notice in embodiment is interesting in light of how much adrenal exhaustion we see culturally in yoga practitioners, and how common knee problems are among yogis who practice very vigorously. Of course, there are very important structural reasons that knees take a beating in so called “advanced” asana practice. But even that may not be completely coincidental—the temperament of a striving practitioner, adrenal stress, and knee problems may cluster together for more reasons than one.

The pancreas is a dual-function gland, having both endocrine and exocrine functions. Although physically it is at approximately the same level as the adrenals, its reflex point is above that of the adrenals, right at the center of the solar plexus. Its endocrine function is its production of insulin and other hormones. It monitors our blood sugar and secretes insulin to keep the body sugars in balance thus contributing to the regulation of energy production. In its organ, or exocrine function, pancreas also secretes important digestive enzymes into the duodenum. Its digestive juices flow via a duct that it shares with the liver into the duodenum at a transition point in the digestive process where the acid secretions of the stomach, which are so important in the first stage of digestion, need to be tamed by the alkalizing pancreatic secretions. This neutralizing of the stomach acids allows the chyme (the food) to proceed to its next step of being absorbed into the body. The pancreas also provides an alkalizing effect beyond the digestive tract, throughout the entire body, and may be an important player in providing anti-inflammatory agents to the body as a whole.

In embodied asana practice, the pancreas—in its glandular function—is the point around which our hands-to-tail and feet-to-head supports are organized. Hands-to-tail and feet-to-head is a glandular and skeletal organization of connecting forces flowing through the pancreas itself. It involves spacial orientation. It has the lightness that is expressed through its glandular source. If the hands-to-tail and feet-to-head forces are not going through the pancreas it is not the support that we are referring to in these terms.

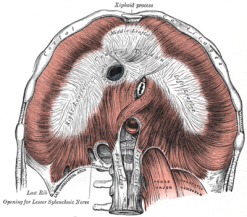

The Thoraco Body

The thoraco body is almost certainly a visible and palpable structure, although no anatomist has yet to describe it. It is likely embedded in the central tendon of the diaphragm right behind the xiphoid process. It is a key player in breathing and regulating the freedom and rhythm of the thoracic diaphragm. It works synergistically with the coccygeal body to initiate breathing.

The thoraco body is almost certainly a visible and palpable structure, although no anatomist has yet to describe it. It is likely embedded in the central tendon of the diaphragm right behind the xiphoid process. It is a key player in breathing and regulating the freedom and rhythm of the thoracic diaphragm. It works synergistically with the coccygeal body to initiate breathing.

At the front of the breathing diaphragm in the thorax, the thoraco body is at the opposite and furthest end from the coccygeal body below. They are structurally connected to one another by the tissues of the diaphragm proper and its stem that is continuous to the coccyx. The coccygeal body initiates inhalation from the back and below and the thoraco initiates breath from the front and above. They are partners.

Where these bodies live have remarkable similarities as well. Each is housed in the immediate region of an important diaphragm and each has a small triangular shaped bone cradling it. Both of these diaphragms are intimately involved in breathing. When their respective diaphragms move, these bones—the xiphoid process and the coccyx— move as well. When breath comes in the xiphoid process waves forward in response to the widening of the thoracic diaphragm. Likewise, as the pelvic diaphragm widens the coccyx waves backward. In each of these movements, in both places, between the gland and the bone we feel an expanding of prana, like a breath of fresh air itself, coming right into the space.

One of the symptoms of a soft and open thoraco and a connection between the thoraco and the coccygeal, is a light widening of the breath at the back of the diaphragm around the lower ribs, through the thicker portions of the crura (its stem), and all the way down the spine. When the thoraco is soft and awake the diaphragm moves like a feather in a breeze with the breath.

The thoraco body is above manipura and below anahata—the level at which we rise into the upper chakras and begin to evolve out of an excessively self-centered existence. This is a time and place for reassessing our place in the world and beginning to put our own personality, wants, and supposed needs, into a larger perspective. We are evolving into a more community oriented vision of life and making decisions about how to proceed. Acceptance and security in the lower centers forms a foundation for a further deepening of caring and the capacity to love. Now we can help others and humanity as a whole to continue to prosper. We have the opportunity to grow into more wisdom.

The Heart Bodies

The heart bodies, the sinoatrial (SA) and the atrioventricular (AV) nodes, are part of the cardiac conduction system. They regulate the beating of the heart by transferring electrical impulses along the cardiac muscle and sparking the polarization and depolarization of cell membranes. They function in conjunction with the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and the vagus nerve. A wave of excitation spreads from the SA node through the atria and stimulates the AV node. The AV delays the impulse approximately 0.12 seconds ensuring that the atria have ejected their blood into the ventricles before the ventricles contract. The AV node also protects the heart from an excessively fast rhythm.

The heart bodies, the sinoatrial (SA) and the atrioventricular (AV) nodes, are part of the cardiac conduction system. They regulate the beating of the heart by transferring electrical impulses along the cardiac muscle and sparking the polarization and depolarization of cell membranes. They function in conjunction with the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and the vagus nerve. A wave of excitation spreads from the SA node through the atria and stimulates the AV node. The AV delays the impulse approximately 0.12 seconds ensuring that the atria have ejected their blood into the ventricles before the ventricles contract. The AV node also protects the heart from an excessively fast rhythm.

When the heart is bisected, as it often is in anatomical examination, it appears at first look to be two separate pumps that are side by side. But anatomically the heart is actually composed of a long rope-like shaped muscle that wraps around itself to form the heart’s chambers. It is its helical shape that creates the twisting and untwisting, or wringing action, of the heart muscle in response to the electrical stimulation that allows for the ejection of blood and the suctioning of cardiac filling.

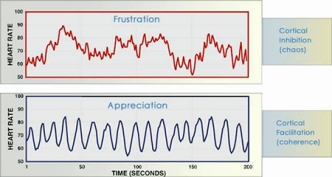

Heart Rate Variability A balanced autonomic nervous system will allow for irregular rhythms of heart beat based upon emotional and physical experience. The normal and healthy variability of heart rhythm is under the control of the autonomic nervous system and the vagus nerve. In health the beating heart is surprisingly irregular as it adjusts to immediate circumstances and needs. The changing rhythm shows resilience and ability to respond. This ability to respond is called heart rate variability, or HRV. Heart rate variability is a measure of the beat to beat changes in heart rate. A decrease in heart rate variability is a marker of stress and is associated with many disease processes, is symptomatic of stress, and is in itself stressful to the heart. It is also associated with aging in general. Although the variability may change with aging, we do have the option of maximizing our HRV at any age.

Yogicly speaking we can certainly assist in keeping the resilience of our heart by consciously softening and relaxing it and by developing and maintaining resilience in our autonomic nervous system. Obviously, many of the practices of yoga are directed toward creating this balance through the “ha” and “tha” of everything we do. One notable effect of yoga practice that has been scientifically observed is that lengthening the exhale has the effect of slowing the heart rate. Inhale hastens the pace and exhale lengthens it. You can feel this easily by taking your pulse while you inhale and exhale.

Joyful emotions create more coherence in our heart rhythms whereas stressful emotions create a more ragged and erratic rhythm. Below is an image from the Heart Math web site depicting heart rhythms in stress and frustration versus during joy, appreciation, gratitude and the like. The lower image is a more coherent rhythm.

Our heart and our brain are in constant communication with one another. Our heart sends more signals to the brain than our brain does to the heart. A feedback loop is created between heart and brain. These signals significantly affect brain functions, including emotional processing and cognitive abilities. A stable and coherently functioning heart supports cognitive ability and reinforces positive feelings and emotional stability. Positive emotions generate increased heart rhythm coherence and the sustaining of positive emotions and coherent heart rhythms profoundly effects how we perceive, think, feel, and act.

Through yoga study we have learned that the center of the individual is not the brain, but the heart. New research into the heart’s functioning is pointing to the importance of our heart as support for all mental and emotional functioning. The very decisions that we have assumed to be made by the brain may be determined by the heart even before we ever “think” about them. We can certainly infer that, ”Coming from the heart” has physiological as well spiritual implications.

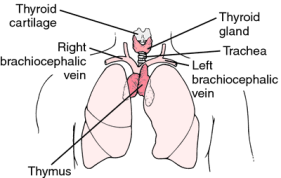

Thymus Gland

The thymus gland is settled just above the heart, behind the body of the sternum, and just below the manubrium. It is a lymphoid organ and functions in conjunction with bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes, among other tissues, to produce the body’s immune response. The thymus works especially closely with bone marrow. Along with other blood cells, bone marrow manufactures white blood cells, called B-cells. B-cells travel to the thymus and are matured into T-cells. The two most abundant lymphocytes are B-cells and T-cells, produced respectively by bone marrow and thymus. (Think B-cell, bone and T-cell, thymus.) T-cells assist other white blood cells in immunological function. They destroy viruses and tumor cells, can “remember” past infections so that immunity remains for an extended period, and are self regulating.

Thymus is a powerful presence within. Our thymus gland is busy transforming—sometimes called maturing—B cells into T cells for their highly specific work. The thymus releases these cells into the blood where they scour through, cell by cell, searching out antigens and foreign substances with the full intent to eradicate them. They kill these dangerous invaders for the sake of the greater good. T-cells are like alert foot soldiers traveling through the blood and lymphatic system, dedicated to maintaing the peace by destroying the enemy through hand-to-hand combat.

In yoga we often speak of valor and bravery in the thymus region. Its integrity and strength supports the shoulder girdle and is a critical contribution to the strength that is necessary for postures like arm balances. The thymus gland provides determination and pulls together what may otherwise be fragmentary actions that strain muscles in the endeavor to hold ones weight. Valor in the thymus region of the upper thoracic area has the foundation of love underneath it in the heart. True valor is based in love and love gives depth and softness to our determination.

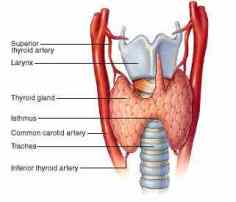

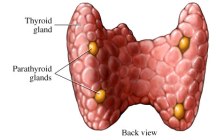

Thyroid and Parathyroids

The thyroid gland is the first of the body’s endocrine glands to develop, around the 24th day of gestation. In the full grown body the thyroid is situated on the front surface of the neck lying on the larynx and the trachea. It moves up and down in swallowing. Thyroid is one of the largest endocrine glands, normally extending from C5 to T1. The thyroid governs the basic metabolism in all the cells controlling how quickly the body uses energy. Its hormone production regulates the body’s sensitivity to other hormones. Thyroid hormone production is under the control of the anterior lobe of the pituitary which is regulated by the hypothalamus.

The parathyroids are located on the rear surface of the thyroid gland. There are usually four parathyroids and each one is about the size of a grain of rice. The parathyroids regulate calcium in the bones and blood.

The parathyroids are located on the rear surface of the thyroid gland. There are usually four parathyroids and each one is about the size of a grain of rice. The parathyroids regulate calcium in the bones and blood.

The thyroid regulates cellular metabolism and cellular respiration. Together, the thyroids support our voice and the structure of our neck. Embodying the thyroid region is helpful for experiencing directly how every cell in the body is awake, alive, and breathing—cellular awareness. Developing cellular awareness is a key for witnessing directly how intelligence and light are manifesting into the form of our own body. When cellular wakefulness is our personal experience, it becomes easy to recognize that it is everyone else’s nature, as well. Realizing this is a giant leap forward in understanding the unity principle in yoga philosophy from an embodied perspective. We know that we cannot be the only ones who are vibrating with this awake, alive, life-force. We spontaneous open to others with the same knowledge and acceptance of their nature…even if they are completely unaware of it within themselves.

Skeletal correlations of the thyroids are to the humerus and elbow, and of course to the neck itself. The thyroid humerus connection is useful in asana. We notice that when thyroids are effectively engaged our upper arms feel clearer and more integrated. This is especially important when we bear weight on our arms. Thyroids provide the fullness of the neck’s circumference and its length.

The thyroid supports the neck inward and upward from the front and the parathyroids support inward and upward from the back. Their support narrows coming together into a fine point that pierces the soft palate, taking us right to the midbrain and making the head light. Collapsing in the thyroids is common in posture and movement. We often see it in ourselves and our yoga students as a neck that sags forward while the occiput drops down and the chin rises. When the thyroid is balanced in the neck we feel the diffusion of its life force through all the body cells. When it is collapsed or hardened, we don’t.

The Carotid Bodies

The carotid bodies are two clusters of chemoreceptor cells located near the bifurcation of the carotid arteries, under the jaws, in the sides of the neck. They detect changes in the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the blood and are sensitive to the blood’s temperature and pH. They are composed of glomus cells like those found in the coccygeal body at the bottom of the spine. The glomus cells secrete neurotransmitters and signal the brain to regulate the rate and volume of breathing. The carotids are the most highly vascularized tissues in the human body, second only to the thyroid.

The carotid bodies are two clusters of chemoreceptor cells located near the bifurcation of the carotid arteries, under the jaws, in the sides of the neck. They detect changes in the oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the blood and are sensitive to the blood’s temperature and pH. They are composed of glomus cells like those found in the coccygeal body at the bottom of the spine. The glomus cells secrete neurotransmitters and signal the brain to regulate the rate and volume of breathing. The carotids are the most highly vascularized tissues in the human body, second only to the thyroid.

The skeletal correlate for the carotid bodies is the entire vertebral column. This includes the occiput, which is not technically part of the vertebral column but is structurally and functionally continuous with the spinal vertebrae. The carotids give levity from each side of the spine allowing the vertebral column to dangle downward. Activation of the carotids in asana helps us to feel the spaciousness of the spine.

Elongating the spine from the carotids is easy. The coccygeal is reaching away providing a pull from below as the carotids simply hover upwards.

Space and levity in the carotid bodies supports the occiput, the jaw joints, and the width of the soft palate. When the carotids are not allowed their full function we experience heaviness in the head and compression into the occiput. Softening and widening the base of the tongue and feeling space in the jaw joints is helpful. When the carotids are spacious and awake and the tongue soft the brain can rest.

Pituitary and Pineal Glands

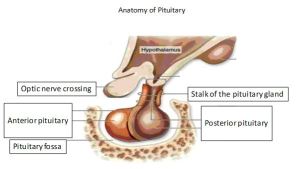

The pituitary gland consists of two lobes, the anterior and the posterior lobes, and a stalk. It sits at the base of the brain in an indentation in the sphenoid bone called the cella turcica. Embryologically, the pituitary’s two lobes emerge from different tissues. The posterior lobe descends down from the hypothalamus in the brain and the anterior lobe rises upward, forming from tissues in the mouth. The anterior lobe does most of the secretion of hormones, while the posterior lobe secretes neurohormones that in turn stimulate the secretion of pituitary hormones. The hypothalamus links the nervous system to the endocrine system through the pituitary.

The pituitary gland consists of two lobes, the anterior and the posterior lobes, and a stalk. It sits at the base of the brain in an indentation in the sphenoid bone called the cella turcica. Embryologically, the pituitary’s two lobes emerge from different tissues. The posterior lobe descends down from the hypothalamus in the brain and the anterior lobe rises upward, forming from tissues in the mouth. The anterior lobe does most of the secretion of hormones, while the posterior lobe secretes neurohormones that in turn stimulate the secretion of pituitary hormones. The hypothalamus links the nervous system to the endocrine system through the pituitary.

Pituitary secretes nine known hormones that regulate the following:

- Growth

- Blood pressure

- Sex organ functions

- Thyroid gland function

- Metabolism

- Water regulation and control through the kidneys

- Temperature regulation

- Pain relief

- Some aspects of pregnancy and childbirth

- Breast milk production

In yoga practice the pituitary relates to the “ha” of hatha yoga, the pingala nadi, and the sympathetic aspect of the autonomic nervous system. It is inhale and expansion. We associate it primarily with aspiration, brightness and clarity, and an outward orientation of mind. It is relatively forward in its place under the brain and governs the upward gaze in back bending and surya namaskar.

The pituitary is balanced by the pineal, which is relationally back brain, and they pivot, rising and falling in relationship to one another around an arc within the brain formed by structures of the limbic system.

Pineal Gland

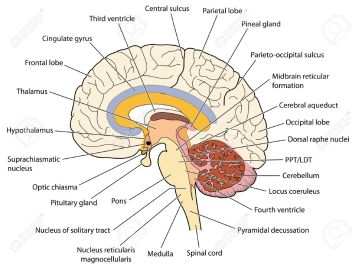

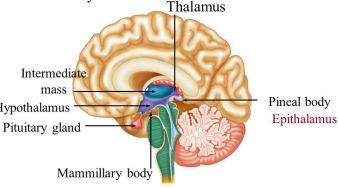

Situated near the center of the brain, above and behind the pituitary, the pineal gland is a small endocrine gland, shaped like a pinecone, about the size of a grain of rice, and reddish-brown in color. Like the pituitary, it is a midline structure and is tucked in a groove between the two hemispheres of the brain, snuggled up near the thalamus. The thalamus is involved in regulating consciousness, sleep and alertness.

Situated near the center of the brain, above and behind the pituitary, the pineal gland is a small endocrine gland, shaped like a pinecone, about the size of a grain of rice, and reddish-brown in color. Like the pituitary, it is a midline structure and is tucked in a groove between the two hemispheres of the brain, snuggled up near the thalamus. The thalamus is involved in regulating consciousness, sleep and alertness.

Like the pituitary, pineal is intimately involved in converting nervous system signals into endocrine function. The pineal is stimulated by the light-dark cycles of day and night, and produces melatonin to make us sleepy at the appropriate time. Regular rhythms of sleeping and waking are critically important for maintaining good health and their balance provide the basis for learning and growing on all levels. Excessive exposure to light at night interrupts pineal function.

Deep rest is needed as the foundation of effective action. Pineal and pituitary balance one another in this regard. Pituitary governs outwardly oriented consciousness and pineal, a more inwardly directed awareness. In yoga we seek to balance pituitary and pineal functions. Pituitary relates directly to the “ha” aspect of hatha yoga. As part of the sympathetic nervous system and in direct relationship to the pingala nadi, it is useful and important in so many ways for all that we do. It helps us to be vibrant and active in our lives. It gives us our fiery, directed and clear ability to act in the world. It gives us determination and tapas in our yoga practice. Its liveliness drives us to study, to get on our mats to move, and even to sit down to meditate. Aspiration is governed by pituitary.

The pineal relates to the “tha” of hatha yoga, governing restfulness, recuperation, and regeneration. Whereas pituitary relates primarily to the to the “ha”—sympathetic aspect of the autonomic nervous system, the pineal relates to the “tha”—parasympathetic.

Pineal supports “being-ness” while pituitary supports “doing-ness”. The pineal allows us to settle and access to it is critical for witnessing the subtle layers of consciousness that are key in yoga practice. In yoga, the pineal gland has always been associated with higher states of consciousness, spiritual insight, and comprehension.

Modern lifestyle often creates a chronically over stimulated pituitary. Hyper-stimulation of the pituitary leads to the accumulation of stress by locking us out of the inherently satisfying depths of awareness and feeling that pineal offers. Culturally we value acquisition and linear thinking and pituitary is good at that, but at what cost? Once we have obtained or acquired something we need to be able to rest and absorb in order to fully receive and enjoy.

We want the relationship between these two glands to be one of harmony and ease. It is the balance of pituitary and pineal that allows the opening of the third eye, the ajna chakra, where we receive and process inspiration. Hatha yoga is excellent for balancing these glands.

Look at the simple actions of the initiation of surya namaskar. We stand in tadasana. In its best practice tadasana is a place of unity and simplicity. We are going nowhere, and doing nothing—standing in the place of yoga. Then we inhale and we look upward. Inhale and upward gazing are representations and stimulation of pituitary and aspiration. Then we bow forward. As we go forward we roll around the head glands and come into a downward gaze. This relates to and stimulates pineal. All of the movements that follow in a surya namaskar continue to roll around these glands, providing alternating stimulation to pineal and pituitary, helping these glands to come into their natural balance. For this to work, we need to allow the natural movements to take place. It is entirely possible to practice surya namaskar from a completely pituitary perspective. When we are already locked into our culturally hyper-stimulated state, we tend to bring that to our yoga practice as well. Without allowing the pineal to feel the respectful surrender of the bow, without fully giving into the exhale, we just continue to further stimulate pituitary in our asana practice. The basic template of hatha yoga is built around inhale and exhale. It is important, as practitioners that we seriously inquire into what that means in practice. Pituitary is inhale, look up, and aspiration. Pineal is exhale, bow, and surrender. How often do we skip the full surrender of exhale and bow in our asana practice?

Mammillary Bodies

If pituitary is “ha” and pineal is “tha”, the mammillary bodies are “yoga”. Pineal and pituitary are the glands that govern the ajna chakra and the mammillaries govern the sahasrara. Hatha yoga is fully represented here in the head glands.

If pituitary is “ha” and pineal is “tha”, the mammillary bodies are “yoga”. Pineal and pituitary are the glands that govern the ajna chakra and the mammillaries govern the sahasrara. Hatha yoga is fully represented here in the head glands.

The mammillary bodies are a pair of small round bodies, located on the undersurface of the brain at the ends of the anterior arches of the fornix. They are part of the limbic system which controls emotions and emotional responses, including mood, pain, pleasure and other sensations. We know that the mammillaries are related to memory since when they are damaged memory is impaired. The mammillaries appear to be in an ongoing dialogue with all aspects of the limbic system including (and maybe especially) the hippocampus and the amygdala. Hippocampus and amygdala are involved in emotional perception and emotional memory. One of the processes of the amygdala is the generation of fear responses, including freezing, rapid heart beat, and the release of stress hormones. In yoga we have considered the mammillaries to offer just the opposite of the fear responses of the amygdala. We have felt the mammillaries to govern comfort, the sense of having options, feeling steady and at home in body-mind. It is interesting to see how the amygdala and the mammillaries relate to each other structurally in the shape of the limbic system. Each are at one end of the arc of the hippocampus.

The amygdala is more forward and lower than the mammillaries. It is connected via the arc of the hippocampus and the fornix, to the mammillaries. The mammillaries (behind the amygdala and higher) are mid line structures—one on either side of the midline, near the base of the brain. The entire limbic area of the brain, tucked in under the cerebrum has the shape of an arch, lower on the front and back, and higher in the center.

In yoga practice the mammillaries feel to be, ”The guardians of perception”. The mammillaries may be balancing the fear production of the amygdala which is just around the arc of the fornix and through the hippocampus. They form the top of the suspension system that is our glandular body. The sahasrara chakra rises as do the mammillaries. There is a profound element of comfort felt when we embody these structures within the brain. In practice, the mammillaries take us to the place of “yoga”. They bring us to our center, and coming to our center brings us to them. In tadasana or any other posture where we are organized in the natural curves of the spine, not going forward and not going backward, we are invited into this place of equilibrium and ease. When pituitary and pineal are balanced and functioning well, hatha yoga has its functional completion in the effortless embodiment of core. This is the place of of deep meditation and stillness. It is not sleepy or agitated. It is awake, alive, self-aware and calm. Balancing pineal and pituitary function opens the gate to experiencing the true unity of core—through the mammillaries and their connection to sahasrara.

Mammillary Glands are the Fulcrum for Movement of the Pituitary and Pineal Glands

CHART—ELEMENTS, CHAKRAS, GLANDS, BODY REGIONS, QUALITIES, DIAPHRAGMS

Element and Kosa |

Chakra |

Gland |

Body Region |

Quality |

Diaphragm |

Awareness-

|

Sahasrara

|

Mammillary bodies |

Crown of skull |

Awe |

Fontanel |

ConsciousnessIndividualChittamaya Kosa |

Ajna

|

PinealPituitary |

Back brainFront brain |

Inspiration |

Tentorium cerebelliSoft palate |

Carotids |

Vertebral column |

Gateway |

Tongue |

||

SpaceAnanadamaya Kosa |

Vishuddha Throat |

ThyroidParathyroids |

Humerus and elbow |

Communication Offering |

Vocal diaphragm |

AirVijanamaya Kosa |

Anahata Heart |

ThymusHeart Bodies |

Manubrium, shouldersSternal area, forearms, wrists |

Love |

Thoracic inlet |

Thoraco body |

Xiphoid process, lower ribs |

Giving and Receiveing |

Thoracic diaphragm |

||

FireManomaya Kosa |

Manipura Navel and Solar Plexus |

PancreasAdrenals |

Hands, tail, feet, headHip joints, femurs, knees |

CommunityTapas, Fortitude |

Mesentery and peritoneal sac |

WaterPranamaya Kosa |

Svadhistana Sacral Plexus |

Gonads |

Ankles, forelegs, and pelvic halves |

CreativityMobility |

Lower peritoneal sac |

EarthAnamaya Kosa |

Muladhara Root |

Perineal BodyCoccygeal Body |

Feet |

Stability |

Pelvic diaphragmArches of feet |

Greetings Patty~ Our Embodyoga West 300-hour teacher training in Folsom is experiencing the body-mind concepts of the grandular system this very week-end through your shining stars, Karen Miscall-Bannon and Stacy Whittingham! Your “yoga pants on the ground” in California are a treasure trove of knowledge, heart, and energy. The intelligent wisdom of these ideas are being shared so skillfully by this duo of Embodyoga teachers who are inspiring another group to embody this art so that we can pass it on and live it! Karen and Stacy are so well-loved and respected for the authenticity, humor, and finesse that define their individual styles. We students feel so very lucky and privileged to be able to learn from the very best on the West Coast. Namaste’ and blessings to you~

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Lori, I am positively delighted to hear that you are in the training program in Folsom and enjoying this work so much! Thank you for reaching out to me with your enthusiasm. I appreciate it from the bottom of my heart. Happy Trails!!

LikeLike